Working toward legislation to curb light pollution in Illinois.

|

|

current page: |

Outdoor Lighting and SafetyHuman vision is limited in low-light situations. Before the development of artificial light sources, the night belonged to nocturnal creatures, whose senses are adapted for darkness. It seems likely that if there wasn't a bright Moon up, our cave-dwelling ancestors spent the nights at home, huddled by the fire; the darkness held increased danger of accident or predator. In the era of draft animal and wagon, lamps were added to shine out ahead so the driver could see where the road was; still, nighttime was generally the time to be at home, rather than traveling. Today, we still have concerns about what dangers may lie in the darkness. However, we don't want to limit our activity to daylight hours. Our vehicles travel much faster than wagons. Our worry about being attacked by a predatory animal has morphed into one about being attacked by a human criminal. We look to artificial lighting to protect us during our nocturnal activities, and retain a primal instinct to feel safer when in a brightly lit area. But in practice, does adding light always make us safer? Considering the many costs of lighting the night, as discussed on other pages of this website, we need to start looking in more depth at real, practical outcomes when discussing lighting and nighttime safety. On this page, we'll visit just a few principal aspects. |

Roadway Lighting

|

|||||

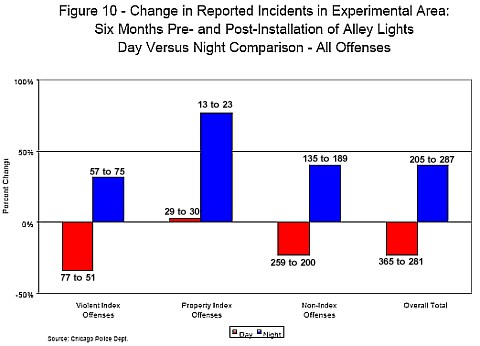

Lighting and CrimeArtificial lighting allows us to conduct all sorts of activities at night, when there would otherwise not be sufficient natural light to see what we're doing. It is also used to let us see things like buildings, signs and monuments after dark. But there is another major component of lighting use, which is different than the activity-oriented ones: Eliminating darkness, where criminals might be lurking. Hundreds of thousands of the outdoor lighting installations in our state were installed with crime fighting as their principle function; how well are they serving their intended purpose? The answers, from real-world studies, might surprise you. In 1998, the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority undertook a test program to evaluate what effect increased nighttime illumination levels would have on crime rates in some areas which had been suffering from high levels of criminal activity10. Two eight square-block areas were chosen which had similar crime rates; one served as a control, while in the other, alley lighting was increased by replacing the existing 90 Watt lamps with 250 Watt ones (approximately three times the light output). Crime data, provided by the Chicago Police Department, was compared for the test area for one year before and one year after the lighting change; data for both the test area and the control area were compared for six months before and after the change, to detect any general change in the overall crime rate in the City during the test.

The startling increase in nighttime crime after the increase in alley lighting is only partially mitigated by looking at the crime data from the control area for the same two time periods. In that area, the rate nighttime violent offences did not change, and overall nighttime crime went up 19%; daytime crime overall went down 21%. Other studies of crime rates and artificial lighting show mixed results, too11. When citizens are polled, the tendency is for them to respond that they feel safer in brightly lit areas, but statistics do not indicate that most crime-plagued areas are functionally made safer by increased lighting alone. Indeed, increased crime occurring with increased lighting, as in the Chicago study above, may be the result of people feeling safer when they actually aren't, thus being lulled into taking fewer anti-crime precautions.

Glare, Safety & Crime Poor lighting practices can even make the night more dangerous. As this pair of photos illustrates, when glare is present, the eye loses sensitivity to fainter light (just like the camera did in these photos); shadows become deeper, and when the glare is removed, the eye takes an appreciable time to regain its dark adaptation. The two photos are of the same scene, taken in succession; the first is overwhelmed by the glare of the streetlight; the second shows the scene with that light blocked by the photographer's hand. Is that streetlight making this area safer?

(In case you didn't notice, the same human figure is standing under each of the four streetlamps, and also in both versions of the double photo in the previous paragraph.) Lighting As A Deterrent If you own or manage property, you are probably concerned about keeping it safe from theft or vandalism. Lighting it up at night seems like a good idea, doesn't it? It is obvious from looking at the above photos that poorly engineered lighting can actually provide the criminal with "cover"; deep shadows to lurk in, while the glare from the lights hides them from observers' eyes. But does lighting up an area effectively keep criminals away? Not necessarily; sometimes it attracts them. School districts in Washington, California, Texas and elsewhere, forced to shut off security lighting around their schools due to budget cuts, have found that their vandalism problems did not subsequently increase; in most cases, they actually decreased appreciably after the lighting stopped12. This result would not happen in every instance where "security lighting" is in use, but it does point up the fact that light, or its absence, is definitely not the only factor in determining the likelihood of crime; sometimes it is not even one of the more important ones. "Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design"13, or CPTED, is a system for looking at many different physical aspects of an area, and arranging them in a manner to most effectively discourage crime. In CPTED, both daytime and nighttime illumination is one important factor, and "more is better" is not assumed to be the case. Glare, shadows, light trespass, overly bright nighttime illumination, and widely uneven illumination are all recognized as creating undesirable, unsafe situations14,15. Footnotes and Additional Resources: | |||||

The article Outdoor Lighting and Crime Prevention on this website delves into these issues in greater depth. |

|||||

|

There are many articles and studies available on the Internet about light, safety and crime. Below, we give links to some which we find to be well-written synopses of some of the topics touched upon on this page, and some studies with hard data; you will find more on the Resources> Links page of this website. 1 The Illinois Department of Transportation's 2007 Illinois Crash Facts & Statistics lists 422,778 accidents, with 103,156 injuries and 1,248 deaths in that year. From the accident total, 65% occurred in daylight, 16% on lighted roadways at night, 13% on unlighted roadways at night, 4% at dawn or dusk. 2The 2007 IDOT report also has breakdowns of accidents by roadway type and location. 3A report on rural intersection lighting from the Transportation Research Board (Canada), 2005. 4A study comparing lighting options on urban freeways from the U.S. D.O.T., 1994 5AASHTO-CEE chapter on roadway lighting & environmental stewardship. 6A Transportation Research Board study on human vision under real-world roadway lighting conditions. 7A Rensselaer/LRC report on lighting engineering focused on reducing stray light levels. 8A Istituto di Scienza e Tecnologia dell’Inquinamento Luminoso (Italy) study on roadway lighting and light pollution. 9A 2003 study (U. of Virginia/Virginia D.O.T.) on analyzing need for roadway lighting on a case-by-case basis. 10 Chicago Alley Lighting Project - Final Evaluation Report (2000). 11"Outdoor Lighting And Crime, Part 1: Little Or No Benefit" and "Part 2: Coupled Growth", B.A.J. Clark, 2003. 12A report from Peninsula School District, Gig Harbor, Wa. 13Wikipedia has a good introductory article about CPTED. 14A report from the Virginia Crime Prevention Association on CPTED (2005). 15The International Clearinghouse on CPTED. |

Return to Page Top |

|||

light pollution Illinois Chicago Cook County DuPage County Will County Springfield energy enviromnent global warming anti light pollution legislation lighting ordinances |

|||