| |

Here we have a typical household DVD player. In Standby mode (in other words, plugged in, but "shut off"), it draws less than 20 milliamps, or about 2 watts. Yes, it should be unplugged when not in use, to conserve that power.

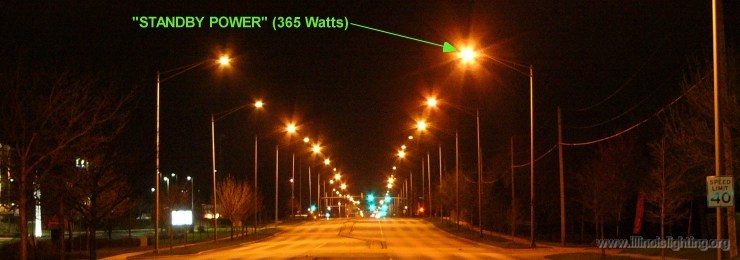

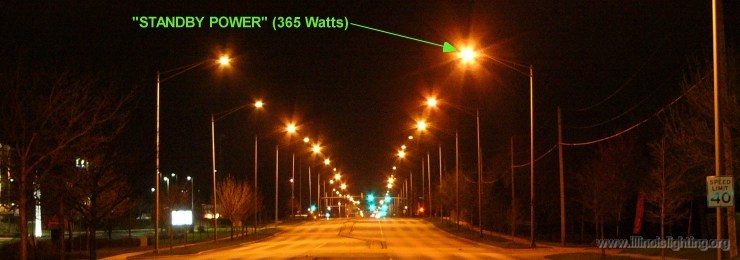

Here we have a suburban street, photographed at about 1:00am on a Saturday morning. The rate of traffic is low; less than one vehicle per minute. Yet, the roadway is illuminated as if traffic was very heavy; scores of streetlamps are operating (with, in this installation, 310-watt lamps, which with ballast, draw about 365 watts each)-- about 50 are visible in this photo alone. In effect, they are all on "standby", waiting until the next evening, when traffic levels may be high again.

How is it rational to focus on the unused DVD player's 2 watts of power consumption during the wee morning hours, when on the street outside the house, thousands of watts are being consumed unnecessarily? If this roadway (and thousands of others like it) truly has high enough vehicular and pedestrian traffic levels and safety hazard levels during the evening hours to make this amount of illumination cost effective, but those levels change this drastically during the night, it is only common sense to alter the illumination level throughout the night, too.

At times when an energy-consuming device isn't serving any really necessary purpose, unplug it.

"Phantom load" may drift away in ghostly wisps from our unguarded outlets. But the energy waste associated with many common outdoor lighting practices is more like Godzilla storming through the streets of Tokyo-- nothing phantom-like about it. Besides "monstrous" waste from leaving lights running when they aren't needed, we also see gargantuan amounts of waste from grossly inefficient light fixtures. "Phantom load" may drift away in ghostly wisps from our unguarded outlets. But the energy waste associated with many common outdoor lighting practices is more like Godzilla storming through the streets of Tokyo-- nothing phantom-like about it. Besides "monstrous" waste from leaving lights running when they aren't needed, we also see gargantuan amounts of waste from grossly inefficient light fixtures.

This can be witnessed any night while flying over an urban area like Chicagoland; while looking down, you are not assaulted by glare coming up off the illuminated streets and other outdoor areas -- you see the direct glare of thousands of lights which, for some absolutely absurd reasons, are shining their energy up into the sky, rather than down into some area of human activity.

We address this issue of misdirected light in more depth on the Lighting Practices pages of this website, but to continue the concept of how very "not phantom-like" this waste is, let's look at the performance of a sample streetlight fixture which is in current production.

This streetlight is similar to many we see in our towns and cities today. The "Victorian" style is very popular; it is based on engineering from that period of over a century ago. But applying today's engineering methods to it, we find out where some of our monstrous waste is coming from, seen here on this page in a view of Chicagoland from above at night. This streetlight is similar to many we see in our towns and cities today. The "Victorian" style is very popular; it is based on engineering from that period of over a century ago. But applying today's engineering methods to it, we find out where some of our monstrous waste is coming from, seen here on this page in a view of Chicagoland from above at night.

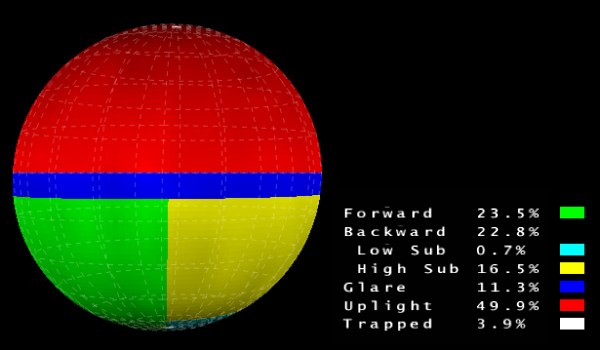

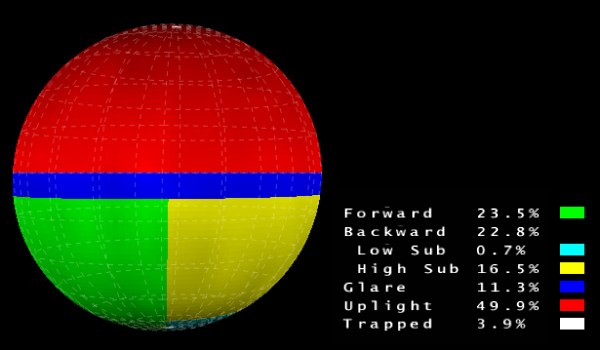

To study the efficiency of a particular streetlight model, we take photometric measurements of its performance; measuring how much light it emits in each direction. From that measurement data report for this particular model streetlight, our analysis software has generated a diagram (below) which documents where the model is sending its light output. The diagram includes a mapped sphere of the light shining forth from the lamp head; the sphere is divided into zones from the Luminaire Classification System*. Also included in the report is a table which lists the percentage of the total light created by the lamp within the streetlight which ends up in each zone.

This report tells us that the target area below and around the streetlight (the green and yellow sections of the sphere) is receiving (23.5 + 22.8) 46.3% of the lamp's output. The "glare zone" (blue), which the Luminaire Classification System defines as just a 10° band below the horizontal line (while in most installations, it should actually reach notably lower), gets 11.3% of the lamp's output. 3.9% of the lamp's output is "trapped"; it never leaves the fixture. This report tells us that the target area below and around the streetlight (the green and yellow sections of the sphere) is receiving (23.5 + 22.8) 46.3% of the lamp's output. The "glare zone" (blue), which the Luminaire Classification System defines as just a 10° band below the horizontal line (while in most installations, it should actually reach notably lower), gets 11.3% of the lamp's output. 3.9% of the lamp's output is "trapped"; it never leaves the fixture.

This leaves 49.9% of the lamp's light output to shine upward, away from the ground (red zone). Half of the light from the lamp is going to waste, glaring up into the sky. This luminaire features a 175 watt lamp; with ballast, the unit draws 204 watts. If it operates for a typical 4,230 hours per year, that totals, in one year's time, about 860KWh of electricity consumed (per each streetlight in the installation). Well over half of that energy consumption is DIRECTLY WASTED by shining light into the sky and glare zones, rather than focusing it down where it is useful (which is quite possible, using a fixture designed with 21st Century engineering, rather than to 19th Century standards).

These common forms of energy waste are, by no means, phantoms. They are more of a gargantuan monster, howling through our towns and across our nighttime skies, night after night. We must demand better performance from our public lighting.

*FOOTNOTE: If any of the terminology on this page is confusing, please see the definitions on our Encyclopedia of Terms page.

|

|

"Phantom load" may drift away in ghostly wisps from our unguarded outlets. But the energy waste associated with many common outdoor lighting practices is more like Godzilla storming through the streets of Tokyo-- nothing phantom-like about it. Besides "monstrous" waste from leaving lights running when they aren't needed, we also see gargantuan amounts of waste from grossly inefficient light fixtures.

"Phantom load" may drift away in ghostly wisps from our unguarded outlets. But the energy waste associated with many common outdoor lighting practices is more like Godzilla storming through the streets of Tokyo-- nothing phantom-like about it. Besides "monstrous" waste from leaving lights running when they aren't needed, we also see gargantuan amounts of waste from grossly inefficient light fixtures. This streetlight is similar to many we see in our towns and cities today. The "Victorian" style is very popular; it is based on engineering from that period of over a century ago. But applying today's engineering methods to it, we find out where some of our monstrous waste is coming from, seen here on this page in a view of Chicagoland from above at night.

This streetlight is similar to many we see in our towns and cities today. The "Victorian" style is very popular; it is based on engineering from that period of over a century ago. But applying today's engineering methods to it, we find out where some of our monstrous waste is coming from, seen here on this page in a view of Chicagoland from above at night. This report tells us that the target area below and around the streetlight (the green and yellow sections of the sphere) is receiving (23.5 + 22.8) 46.3% of the lamp's output. The "glare zone" (blue), which the Luminaire Classification System defines as just a 10° band below the horizontal line (while in most installations, it should actually reach notably lower), gets 11.3% of the lamp's output. 3.9% of the lamp's output is "trapped"; it never leaves the fixture.

This report tells us that the target area below and around the streetlight (the green and yellow sections of the sphere) is receiving (23.5 + 22.8) 46.3% of the lamp's output. The "glare zone" (blue), which the Luminaire Classification System defines as just a 10° band below the horizontal line (while in most installations, it should actually reach notably lower), gets 11.3% of the lamp's output. 3.9% of the lamp's output is "trapped"; it never leaves the fixture.